Computational Thoughts

An archive of posts written in the context of the Master’s in Computational Arts at Goldsmiths College, University of London, academic year 2017-2018.

§

27 March, 00h29

All resources for ‘Wordlaces’, including the final essay, the code files, and the texts, are to be found in this GitHub repository.

§

26 March, 23h27

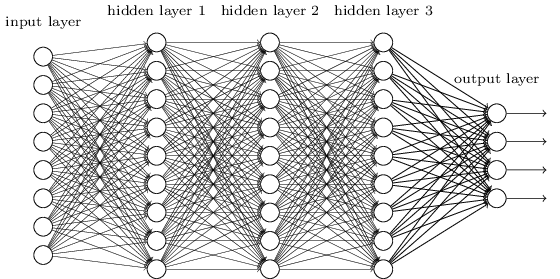

As a little refreshment from essay writing and coding, a little peek at the future of my Natural Language Processing trajectory: NLP with deep learning and Word2Vec:

§

21 March, 12h13

The idea of virtual reality and avatars as intertwined with haptics had never occurred to me. I had envisioned quite the opposite: VR, as a lot of what we see in the cybersphere, as the space where touch, and more generally physicality, can be escaped from, eluded, played with.

Sexuality can be experienced at a distance, with strangers, away from bodies, perhaps from rape. However, pointing out the potential link between the sense of touch and avatars, ‘external’ bodies that are with little doubt a forthcoming step in the development of technologies, is perfectly relevant. It might be worth briefly explosing my first reaction a bit further, as it could have artistic (technoartistic) implications. I mentioned this surprise at what I perceived to be ‘haptic opposites’: on the one hand, the avatar, that I approach from its external aspect (hence a name for it: telehaptics, or the means by which, not unlike Apollo, you may touch from afar); on the other, what I woudl be keen to explore, the idea of private or inner touch as the basis for art, an area which remains greatly unexplored. Are there forms of art that are based on touch as such, as one can say that music is based on hearing, painting on vision, etc.? Seems to me that there isn’t. Dance, for instance, for all its physicality, is still a ‘faraway’ art, with a strong distance between the audience and the performer in a large majority of cases, and massage, say, where touch is really the most central element, is confined to therapeutic or leisurely purposes. The interesting question would be, then, could technology, and a technology that could expand into the haptic dimension, create a medium for the haptic dimension, as scores and recordings are a medium to musical performance, lead to the irruption of yet unexplored, or underdeveloped, forms of art? Coming back once again on that first reaction, I could wonder whether it would be possible, through technology, to overcome the intimacy issues related to touch (which probably for that reason made it the reserved realm of healthcare or very close relationships) and allow for an artistic space to develop where one would willingly lend one’s body to the touch of a haptic artist, as one lends one’s ear to the musician, or the eye to the artist, for one to experience a rarefied, and elevated kind of touching?

That is of course where the two visions coincide: what could be more ideal than a situation where instead of letting someone in, as was my first idea, one could somehow ‘get out there’, for one to experience another type of haptic experience (see p. 37)? That is what an ‘avatar’,

or a ‘Matrix’, could be all about.

David Parisi, Archaeologies of Touch: Interfacing with Haptics from Electricity to Computing, Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press

§

21 March, 11h28

There is an whiff of the steampunk in Tarleton Gillespie. Let us read the conclusive paragraph of his article ‘The Relevance of Algorithms’:

A sociological inquiry into algorithms should aspire to reveal the complex workings of this knowledge machine, both the process by which itchooses information for users and the social process by which it is made intoa legitimate system. But there may be something, in the end, impenetrableabout algorithms. They are designed to work without human intervention,they are deliberately obfuscated, and they work with information on a scalethat is hard to comprehend (at least without other algorithmic tools). Andperhaps more than that, we want relief from the duty of being skepticalabout information we cannot ever assure for certain. These mechanisms bywhich we settle (if not resolve) this problem, then, are solutions we cannotmerely rely on, but must believe in. But this kind of faith (Vaidhyanathan2011) renders it difficult to soberly recognize their flaws and fragilities.

So in many ways, algorithms remain outside our grasp, and they aredesigned to be. This is not to say that we should not aspire to illuminatetheir workings and impact. We should. But we may also need to prepareourselves for more and more encounters with the unexpected and ineffableassociations they will sometimes draw for us, the fundamental uncertaintyabout who we are speaking to or hearing, and the palpable but opaqueundercurrents that move quietly beneath knowledge when it is managedby algorithms.

It is most probably essential today to think about algorithms, and discuss their effects, their relevance, their seeming impenetrability.

Once again I find myself so much at odds with what I perceive as the contemporary ‘mysticism’ around those (which could be, perhaps, an emotional rather than a rational response to these new technological irruptions). This has even been reinforced by my recent foray into machine learning in Rebecca Fiebrink’s class. I read a text about algorithms and I expect something along the lines of, say, an excursus on the steam engine in the mid-19th century, or the electricity in the later years of that same era (one might want to go back, for some crispy comparisons, to Franz Mesmer). The two main issues I see with algorithms are the following: it is not easy to get one’s head around the algebra (just as it is not everyone’s cup of tea to know how an enginge works), and, more blatantly, the imperative of concealment that economic competition imposes on companies. These two combined are quite banal, and it is in fact what my impression has been when learning more about classification, regression, and other algorithms, including neural networks. I see elaborate machines based on sophisticated concepts and techniques, requiring one’s application, the development of one’s knowledge and understanding. There is a whole vocabulary there designed to generate emotions (related to fear, to awe, to faith) which is simply alien to me, and, I would argue, alien to the subject matter: ‘designed to work without human intervention’, ‘deliberately obfuscated’, ‘…must believe in. …this kind of faith…’, ‘ remain outside our grasp’, ‘ prepare ourselves for more and more encounters with the unexpected and ineffable associations’, ‘fundamental uncertainty’, ‘the palpable but opaque undercurrents’. At every line I cannot but think that he is talking about the steam engine, and see novelists writing about British steam-suited-and-booted cosmonauts confronting a Martian invasion. That might be a matter of culture, a cultural gap of some sort? I live in a world where faith, and the unspeakable, seem very distant, either geographically or chronologically. Something gothic, like novels about the Devil and the Spanish Inquisition. Elaborating this sort of ‘poetry’ around technology leaves me perplex and a bit dispirited. Disengaged.

Tarleton Gillespie, ‘The Relevance of Algorithms’, forthcoming, in Media Technologies, ed. Tarleton Gillespie, Pablo Boczkowski, and Kirsten Foot. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

§

20 March, 23h50

Small addendum to the reservoir of Natural Language Processing concepts:

In computational linguistics and computer science, edit distance is a way of quantifying how dissimilar two strings (e.g., words) are to one another by counting the minimum number of operations required to transform one string into the other. Edit distances find applications in natural language processing, where automatic spelling correction can determine candidate corrections for a misspelled word by selecting words from a dictionary that have a low distance to the word in question. In bioinformatics, it can be used to quantify the similarity of DNA sequences, which can be viewed as strings of the letters A, C, G and T.

Different definitions of an edit distance use different sets of string operations. The Levenshtein distance operations are the removal, insertion, or substitution of a character in the string. Being the most common metric, the Levenshtein distance is usually what is meant by “edit distance”. (Wikipedia)

I already thought of playing with this literarily: words are related to each other by minimal edit ‘steps’, especially, in a very limited version, only by the substitution of one letter by another (keeping the length intact). One could envision ‘word paths’ (which are, in fact, closer to tesselations) where the proximity between various words would be made visible, as well as trajectories leading from one word to another. For instance:

sing > sink > silk > milk > mink > (minx | monk)

§

20 March, 19h05

Reading chapter 1 (‘The Social Turn: Collaboration and its Discontent’) of Claire Bishop’s Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, London, New York: Verso, 2012, especially quotes around passiveness, action, and participation, such as the following two:

“At present, this discourse revolves far too often around the unhelpful binary of ‘active’ and ‘passive’ spectatorship, and – more recently – the false polarity of ‘bad’ singular authorship and ‘good’ collective authorship.” (8),

and

“Given the market’s near total saturation of our image repertoire, so the argument goes, artistic practice can no longer revolve around the construction of objects to be consumed by a passive bystander. Instead, there must be an art of action, interfacing with reality, taking steps – however small – to repair the social bond.” (11),

I cannot but wonder how my own experience fits within this discussion.

My own experience, that is, with passiveness and action, with the participatory and, one could say, the imparticipatory forms of art. A first remark, which cannot go unmentioned, is that participatory art, in the common acception of the term, is quite alien to my trajectory, quite remote, as it were, as if a foreign tradition. But also, the other fact that the distinction between active and passive is not lifted at all for that reason, but runs through and between art works and their makers.

Even if I only focus on the ‘imparticipatory’ most of the time, the division between the ‘passive’ (bad) and ‘active’ bystander, and works made for it, is extremely active (it has been active to the point of inner civil war and mental breakdown in the past). And approaching participatory art even in the most superficial way I notice that I instantly produce the same division: is this piece, is this artist, rather in the passive or the active camp, and therefore should I devote time to them, piece or artist, or not bother? It is interesting that in what Kaprow condemns as to be rejected (‘film, poetry, cinema, architecture’, etc.) in favour of the happening, the radically new, I see countless examples of the radically new, and the radically engaging (or perhaps rather the ‘demanding radical engagement’, which more often than not just means those works, those artists, are not often truly experienced, at best admired from afar or studied by specialists). Conversely, I find in the participatory, as in the conceptual, a lot of the unengaging, the easy, the shallow, against which the ‘traditional’ artists who paint, write, sculpt, etc., have stood for centuries. Something, it seems, repeats itself in the history of art, most probably as different from what preceded it as it is redundant: the insurrection of the (good) ‘active’ against the (bad) ‘passive’ and is afoot within, and across, both the participatory and the imparticipatory. P.S: another brand of unhelp, and false polarity, occurs with the value jugement of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ with regard to the (perceived) passiveness and activity of certain practices, as well as for the question of ‘singular’ and ‘collective’ authorship in the quote above. Those are, in my view, better approached as logic squares:

| (bad) singular | (good) collective |

| (good) singular | (bad) collective |

| (bad) passive | (good) active |

| (good) passive | (bad) active |

§

20 March, 17h07

A few ideas relating to data sensing:

- imagine a text that would adapt to its environment, to its readers. Following the wave of digitalisation of the late 20th century, and then the machine-awakening of literary practice, texts become adaptive, sentient. Groundbreaking novelists work on narratives that would adapt to a changing, heating world. It starts perhaps with simple description of environments, but rapidly homines fabri yearn for more, and make characters, story lines, appear in the landscape of world literature. An interesting archiving question arises: is it still possible to read the past in that adaptive world? Older texts, and what future eras views as their flaws (canonic example: the Paganism of Antiquity to Christian readers throughout the Middle Ages), could change, leaving no trace of previous world views. In a world devastated by droughts, mass extinctions and climate wars, archaeologists could painstakingly reconstitute, from the small remaining fragments available, the picture of our world. The question of erasure of the past also arises every time dictatorship or political repression of all hues is treated, as is the twisting, corruption of the arts to the dominant system (which becomes a slave of either state, as in Stalinist Russia, or of the global market, as in most of the world today, especially in the USA and the UK): can that lead to questions relating to the ‘unsensing’ in the art? An art robust enough that it does not adapt to certain environments, despite the pressure of said environment? An interesting approach to mid-20th century music, ‘Modernism’, is that unlike contemporary art, most of it has remained unabsorbed, impervious to merchandization (composers have first had to reject its fundamental tenets, notably dissonance and atonality, before being readmitted into the fold) just as it is to ‘popular’ appeal. It may well be that its ‘moribund’ state could be a sign of a stubborn, if subterranean, underworldly, form of life. - Once more it is by going to some sort of extreme, to the edge of the spear, that one makes discoveries relating to a broad range of phenomena. In the Arctic, one of the two climactic extremes of the planet, it is possible to sense climate change more accurately and more directly, and meditate consequences for citizenship and art that could apply to the entire world. A similar gesture can be found in the very focus on new technologies and their social and artistic consequences: exploring the nascent worlds envisioned by early adopters of technology allows researchers and artists to analyse, instead of foresee, fragments of things to come.

- In many Japanese animes, including Psycho-Pass, personal data gathering is pursued much further than in reality: entire countries are monitored using mental health, stress levels, and other very intimate factors. When embedded in narratives of criminal investigation, society is approached with the same dispationate, and somewhat an-ethical eye of the empiricist, seeking to understand and, possibly, control, an environment and its process. Unsurprisingly, in many of these works of fiction, the recurrent theme is political: what are the consequences for the state, for citizenship, for individual and collective decision making, and for the idea of the self. - A step, a very timid, tentative first step, into the Anthroposcene, as humanity is experiencing right now, could be, and is, linked with the question of food consumption and animal welfare. As humankind is able to modify planetary environment, thus discovering the responsibility linked to this newly found power, a minoritary but growing part of it is also extending the argument of power and responsibility not only to the environment as an abstract whole, but to the animals we eat. Just as calls have been made, from Marx to critiques of contemporary hardware production, to make visible the labour necessary to produce commodities, one could imagine sensors that reveal the life and death of animals to people consuming meat.

Jennifer Gabrys ‘ Sensing Climate Change and Expressing Environmental Citizenship’ in Program Earth: Environmental Sensing Technology and the Making of a Computational Planet (Electronic Mediations).

§

19 March, 23h59

Completed the following tutorials (not incredible, but convering a few issues not present in Sentdex):

All the code relating to these can be found in this repository.

§

16 March, 13h30

Another captivating philosophical discovery, primarily because of the rarefied and lustrous style (itself a cause for suspicion), but also because it is rooted in a tradition that I know little of (and am still just as suspicious of, rooted as I am in more continental references), namely English liberal thought, mostly based on Hobbes, Locke, but also Bentham, Mill, and others:

§

12 March, 23h

Completed a series of tutorials related to NLTK:

The result is only a superficial introduction, a warm-up for things to come, but still gives a good glimpse of what is possible with these tools. Here is a repository containing the files produced during these (and future) sessions.

§

25 February, 23h

The Wikipedia page for Natural Language Processing offers a list of important concepts relating to this field of study. It seems a useful thing at this point to sum these up both for memorizing and explanation purposes.

Syntax (the study of sentences, or the linear dimension of language) & Morphology (the study of words)

- Tokenization: separate a text into discrete constituents (mostly words), eliminating punctuation and other characters. A part of the ‘text normalization’

process (see below). - Lemmatization: the process by which the computer groups together different forms of a word (called ‘inflection’) into one: ‘speaks’, ‘speak’, ‘spoke’, ‘speaking’, all belong to the verb ‘to speak’.

- Morphological segmentation: this goes one step deeper, and separates components of words, e.g. ‘speak-ing’, where ‘speak’ is the stem and ‘ing’ is the marker for the continuous aspect.

- Part-of-speech tagging: apply a tag to each word indicating to what grammatical category it belongs, e.g. ‘speaks’ (verb), ‘colloquially’ (adverb), cow (noun), etc.

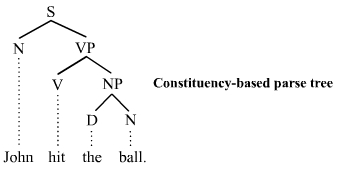

- Parsing: use systematic methods to decompose a sentence into its structure, and therefore understands the function of each element (what is the subject of the verb, its object, what is the complement of what, etc.). This structure is called a ‘parse tree’, as it posits that each sentence can be reduced to a tree-like shape like in the picture.

S = sentence, P = phrase, V = verb, N = noun, D = determiner. One notices that the sentence has a logic, it is not a pure concatenation of words, and in this case has two very important constituents: the verb phrase (VP), and a noun phrase (NP), the identification of which is done through another operation called phrase chunking.

S = sentence, P = phrase, V = verb, N = noun, D = determiner. One notices that the sentence has a logic, it is not a pure concatenation of words, and in this case has two very important constituents: the verb phrase (VP), and a noun phrase (NP), the identification of which is done through another operation called phrase chunking. - Sentence breaking (also known as sentence boundary disambiguation): find the boundaries of sentences in a text.

- Stemming: process a text so that each inflected form (‘speaking’ instead of ‘speaks’, ‘insects’ instead of ‘insect’) is reduced to its stem, which can be useful when one is only interested in the semantic value of words within the text (are the words overall positive or negative, for instance). This is an important part of text normalization, the action of preparing a text before submitting it to analysis.

- Stop word: a word that is filtered out during the text normalization process, that is, removed before the actual analysis takes place. In the context of sentiment analysis for instance (see that entry below), purely syntactic words like ‘the’ or ‘a’ will be filtered out, in order to focus on semantics (such as ‘pizza’, ‘amazing’, etc.).

- Bag-of-words model: a way of simplifying a text to reduce it to a set (bag) of words, disregarding grammar and possibly word order, and only keeping the frequency. This is also known as ‘vector space model’, because each individual term becomes a dimension, and the frequency, or frequency + a weight of importance, among other methods, becomes a value in that dimension (one text becomes a large vector with as many dimensions as it has separate words, with a specific values for each word, e.g., in a simple case, 5 for the dimension ‘apple’ because this words appears 5 times.).

- Word segmentation: in English rather trivial, as words are separated by spaces, but not in all languages (e.g. in Sanskrit), where additional processing must be developed to find the separation between each individual word.

- Terminology extraction: retrieve what are the relevant, important terms or concepts in a given corpus of text.

☙

Semantics (the study of meaning)

- Lexical semantics: determine the meaning of words in context.

- Machine translation: the automation of translation from one language to another.

- Named entity recognition: (NER): determine what words in a text are proper names (individuals, places, etc.), and to what type they belong.

- Natural language generation: the opposite of what has been seen until now, namely, instead of analysing and understanding text, produce text using data and rules.

- Natural language understanding: extract logical structures from human text (a simple example from that could be: ‘John ate the apple’ and ‘The apple was eaten by John’; in both cases the agent is John, even if in the first case he is the subject of the verb and in the second he is the object).

- Semantic role labelling: the actual process for the previous example, and sometimes called ‘shallow semantic parsing’ (see ‘parsing’ above), whereby the computer determines what roles various parts of the sentence play (e.g. what is the agent and the patient).

- Optical character recognition: (OCR): the ability for computers to read text within images (this video introduces deep learning through this specific problem).

- Question answering: program computers to answer human questions, the basis for chatbots.

- Recognizing Textual entailment: not too far from Natural language understanding, this tasks attempts to determine logical entailment (does this piece of text implies that other one, or implies its negation (contradicts it), etc.).

- Relationship extraction: extracts relationships between entities of a text (e.g. feed the computer a novel, see if it can detect what are the interactions between the various characters, etc.). See also the entity-relationship model.

- Sentiment analysis: extract subjective information from a text (alluded to in ‘stemming’ above), especially if the overall mood is positive or negative.

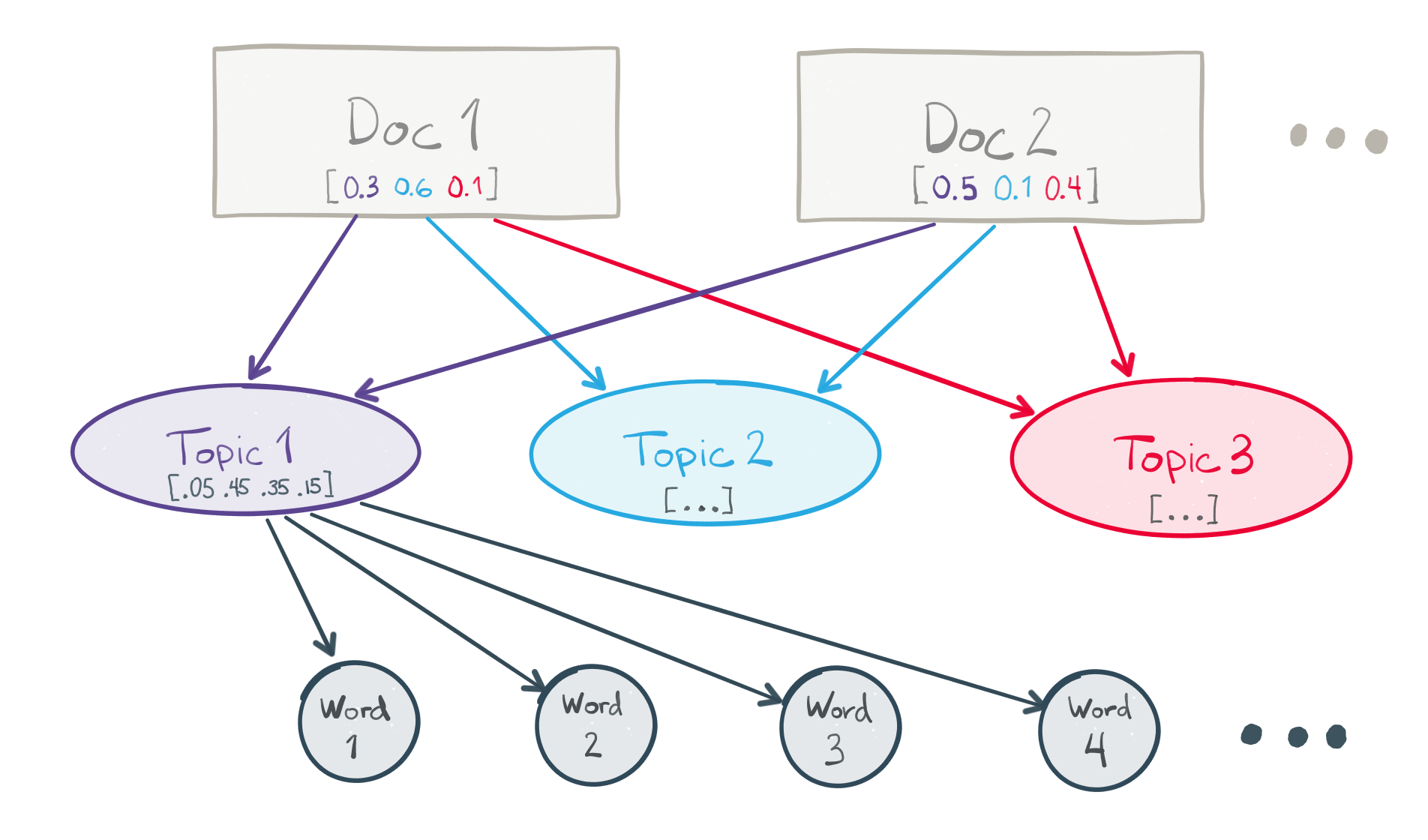

- Topic model: a type of unsupervised statistical model developed to extract ‘topics’ from text corpora. In the conference by Patrick Harrison in the post below (text here), the topic model used is Latent Dirichlet allocation, which uses three layers (documents or texts, topics, words) instead of two (documents, texts) to deal with texts:

- Topic segmentation and recognition: divide a text into various parts, and extract a topic for each part.

- Word sense disambiguation: a domain of ‘lexical semantics’ above, determine what specific meaning a word has in context (among all the ones it can have).

☙

Discourse

- Automatic summarization: produce automatic summaries for texts.

- Coreference resolution: determine which words in a text refer to what entity (in a text, ‘Mary’, ‘Bob’s mother’ or ‘their neighbour’ could refer to the same person). A particular task within this field is anaphora (and cataphora) resolution, namely determine to what entity pronouns refer to (in the sentence: ‘Bob shook his head’, ‘his’ refers to ‘Bob’, and comes after the first mention of the entity, hence is an anaphora – on the contrary, in the sentence ‘When he arrived home, John went to sleep’, the pronouns comes before the entity, and is therefore a cataphora).

- Discourse analysis: tasks related to larger chunks of text, e.g. determine the structure of a text as a whole (is this passage an elaboration, a digression, a conclusion, etc.), or determine speech acts within the text (which are passages that are not fully understandable as simple transfer of information but have performative power, such as promises, orders, etc.).

☙

Speech

- Speech recognition: recognize and analyze oral speech (used for Siri and Alexa for instance).

- Speech segmentation: subdivide a sound stream into separate words .

- Text-to-speech: given a sound stream, produce the written text that was spoken.

☙

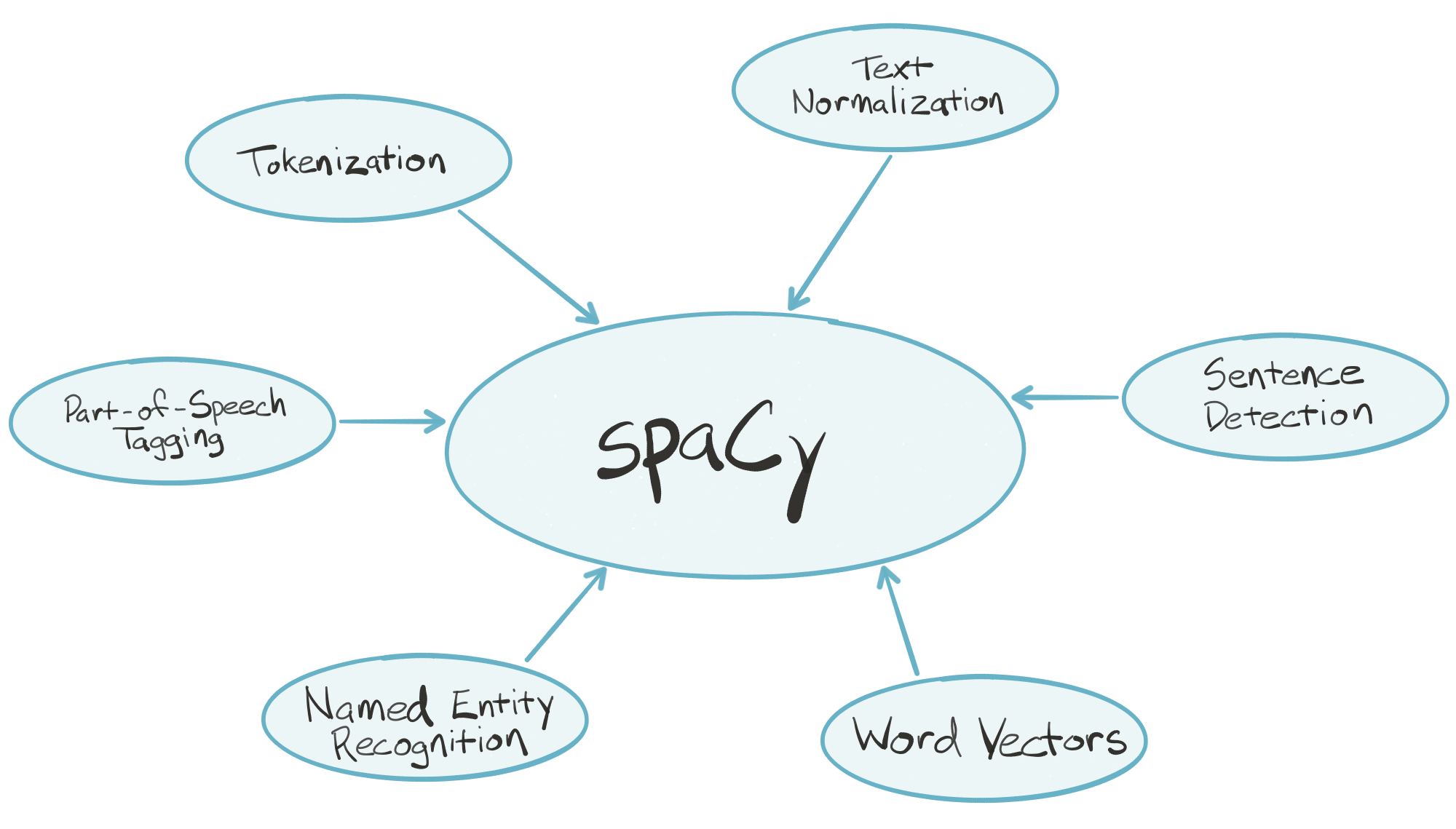

Libraries (see the conference and Jupyter Notebook text in the post below)

- spaCy: “is an industrial-strength natural language processing (NLP) library for Python. spaCy’s goal is to take recent advancements in natural language processing out of research papers and put them in the hands of users to build production software.

spaCy handles many tasks commonly associated with building an end-to-end natural language processing pipeline:- Tokenization

- Text normalization, such as lowercasing, stemming/lemmatization

- Part-of-speech tagging

- Syntactic dependency parsing

- Sentence boundary detection

- Named entity recognition and annotation

- In the “batteries included” Python tradition, spaCy contains built-in data and models which you can use out-of-the-box for processing general-purpose English language text:

- Large English vocabulary, including stopword lists

- Token “probabilities”

- Word vectors’ (from here)

- gensim: claims to be ‘the most robust, efficient and hassle-free piece of software to realize unsupervised semantic modelling from plain text’ (here), and is used in the conference to achieve phrase modeling (the process by which ‘New York’ is recognised as one entity, and not just two words, and ‘New York Times’ as another, all in an unsupervised fashion).

- pyLDAvis: a library to create interactive topic model visualization.

- t-SNE (or t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding): a ‘dimensionality reduction technique to assist with visualizing high-dimensional datasets’ (paper here, scikit class reference here)

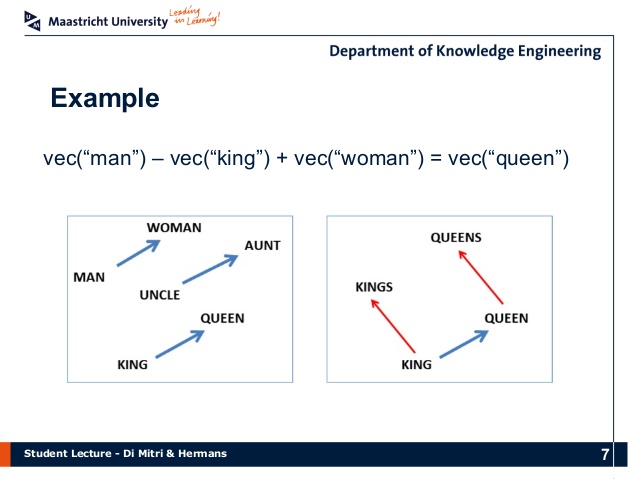

- word2vec (or word vector embedding models): models used to produce word embeddings, that is, the projection of words from a text into a(n often highly complex) vector space, the purpose of which is to create a geometric representation of relationships between words, and their context. Similar words (synonyms, antonyms, cohyponynms, etc.) are close together in that space. From there, it is possible to apply algebraic operations to words themselves, namely vector addition and multiplication. Since vectors and coordinates are in a dual relationship (two mathematical entities almost substitutable for one another, as if one was looking at the same thing under two different aspects), a word like, say ‘female’ is not only somewhere on the space (as a coordinate) but will also exist as a ‘distance’ (a vector) between the words ‘king’ and ‘queen’ (and indeed word2vec allows for operations such as ‘king’ - ‘male’ + ‘female’ = ‘queen’). Other fascinating examples that emerged from the unsupervised process are: ‘sushi’ - ‘Japan’ + ‘Germany’ = ‘bratwurst’, or ‘Sarkozy’ - ‘France’ + ‘Germany’ = ‘Merkel’.

☙

The links mentioned at the end of this video:

- GloVe (Stanford)

- Word2vec (Google)

- Word embedding tutorial (Tensorflow)

- Eigenword (Penn)

- Interactive demo

§

16 February, 18h37

A conference on NLP that displays quite a few concepts on a real example:

The Jupyter Notebook text of this conference on GitHub.

§

16 February, 14h30

The upside of having two concurrent projects is that at least I found more than zero areas of interest…Beside NLP, the parallel topic that came to me is David Harvey’s introduction to Karl Marx’s Capital,

available in book form and as two lecture series on YouTube:

A Companion to Marx’s Capital, Vol. 1 & 2, New York, London: Verso, 2013

‘Reading Marx’s Capital’ on YouTube:

§

14 February, 23h

First steps into Natural Language Processing,

starting, as I’ve done fairly successfully for other computing topics,

by the most basic sources I can find:

§

08 February, 11h00

Recent discovery: Walter Scheidel

Watching this conference, and thinking back on my gradual politicisation during my time in London, as well as a growing consciousness of economic matters, I realise I should probably include various ressources that I went through in the past two years, as they undoubtably shape my current position and my areas of interest. I will mostly include here videos, and in some cases books.

☙

Thomas Piketty, Le capital au XXIe siècle, Paris, Seuil, 2013.

☙

Martin Wolf, The Shifts and the Shocks: What we’ve learned – and have still to learn – from the financial crisis, London, New York: Penguin, 2015.

☙

Paul Collier

☙

David Graeber

☙

Yanis Varoufakis, And the Weak Suffer What They Must? Europe, Austerity and the Threat to Global Stability, London, New York: Vintage, 2017.

—, The Global Minotaur: America, Europe and the Future of the Global Economy, London, Zed Book, 2018.

|

|

§

08 February, 10h00

One voyeuristic idea for a computer ‘vision’ project: an access so intimate and so direct to people’s lives that, walking down the streets, one could perceive, perhaps through a colour filtering or other visual effects on their person, many private aspects of people’s lives. Their mood, of course, but also if they have friends, lovers, illnesses if any, physical processes like digestion, erection or period, what their sex life has been recently, or the state of their finances.

I would also love to see a woman, especially a woman of colour, wear glasses recording her point of view for a day, a week, to keep track of what is perceived as abuse. A computer could then extract that data (transpose remarks from oral to written, pick up on tones, count the number of times physical contact was inappropriate, or keep track of stress levels, etc.) and present that in a way that is graspable by others, or simply give out a precise tally. Something like the other face of the police body worn camera.

☙

A very odd reaction to Safiya Umoja Noble’s article: perhaps what goes against my natural way of thinking is the fact that it starts with race and gender, as the obvious symptom of dysfunction in our societies, to end with economic and geopolitical considerations (such as the globalised production chains and the enduring consequences of imperialism and Western preeminence). My reaction then is to say that I would rather go the other way around: start with the ‘system’, examine its consequences. But it might not even be that, I am not so certain now, more thoughts needed. One major argument in favour of the former approach is that it is like detective work: you start with the crime, the scene thereof, the clues. And you keep tracking and deducing until you found your way to the source, the perpetrator(s).

§

01 February, 10h40

Yet another thought that could be pursued in the context of this class: go back to my philosophical references and reinforce them, in order to reach the mastery required to start formulating my own hypotheses and positions. The central figure in my philosophical development has been Alain Badiou, discovered roughly ten years ago, and to a lesser extent Quentin Meillassoux. These two thinkers offer an interesting angle to approach post-war French thought, as they are at the same time clear representatives of this tradition, engaging actively with core figures of that era (such as Lacan and Deleuze, among many others), while distancing themselves from them. The confrontation between Deleuze and Badiou (thematized by Badiou himself in this small opuscule) is of particular relevance to me, as I tend to perceive the world, the Anglo-Saxon world, as starkly ‘Deleuzean’ (just as I perceive it to be more Jungian than Freudian). This enquiry would be less a matter of ‘application’ of a theory straight into artistic practice, which I often find crude or superficial, but rather an attempt to grasp these theories more profoundly, betting on the fact that assimilating them ‘in the abstract’ will yield results, whether I seek them or not, in my overall orientation and the outlook of my future work.

§

25 January, 10h06

Another, only superficially unrelated topic that came to mind, and that may prove fruitful both on the theoretical side (as it really is theory, and not ‘technique’, one could argue, as in the case of Natural Language Processing below) and on a personal level (where it succeeds in catching my eye, unlike so much analyses of this or that particular phenomenon of the tech world), is a course found a bit more than a year ago by David Harvey offering a detailed reading of Marx’ Capital.

Beside the fact that my being even remotely interested in these things is a direct consequence of the fetid, alienating air of London, which twisted Karl’s mind already back then, it has to be admitted that the course is a prime example of a full theoretical introduction to Marxian analysis, comprising economics, politics, and philosophical dimensions.

I watched two thirds of the videos of volume one a year ago, but could come back to that and set myself the goal of completing the whole cycle in a more systematic way this term.

§

24 January, 21h30

Thoughts on a few research threads.

The first, most obvious one would be to focus on Natural Language Processing, the field of study at the intersection between language and computation, which would give me foundations for my future practice. Two entire courses from Stanford University are available on YouTube, and which could be a substantial trove of material for the weeks to come:

Professor Dan Jurafsky and Chris Manning’s Introduction to Natural Language Processing, and Chris Manning and Richard Socher’s Natural Language Processing with Deep Learning (with perhaps books such as this one as a starter). Python seems to be the obvious language for this enquiry, and starting to study it (here, here or here, although this is altogether too ambitious, and it might be quicker to go for online crash courses, or even cheat sheets).

Another, as yet unrelated topic of enquiry is to get a better idea of the current situation of the AI race, and its geopolitical implications.

I have been surprised not to find many books on the topic straight away (even though they must exist). One of the core questions is the emergence of two poles in the world today, the US and China, with Europe almost entirely out of the picture (the Brexit vote, among many other things, can be read as a geopolitical alignment whereby the UK, when confronted with a touch choice, goes the American rather than the European way), and what that means for Europe’s present and future role in the world. (This is all the more surprising as many European countries are consistently ranked in the top ten in innovation and overall economic activity, see the map of this article for instance.)

§

17 January, 20h26

The search for an interesting app has proved, rather unsurprisingly, difficult. I will start with a list of various attempts, which might help me getting deeper into one of them and perform the walkthrough method, or at least parts of it, on it.

My first impulse can be subdivided into three ‘alleyways’:

- apps developed by writers or word-oriented people of experimental nature;

- useful apps related to literature, philosophy, history, etc., even if not artistic or creative per se;

- other apps the interest of which could be political, economic, or ‘inspirational’, possibly feeding into future projects of mine.

Taking each of these cases one after the other the result so far is the following:

Literary apps:

My dissatisfaction remains more or less complete: my journey started on this page, which lists ten literary apps (1). Most of them, especially ones supposed to be works themselves, have been discontinued. The Jack Kerouack one looks like ones developed by Faber & Faber, discussed below. Even if absentMINDR and Device6 deserve a fair hearing (somewhat difficult as they are not available for download any more), they seem altogether far from triggering the reaction I have when facing, or suspecting that I am, a new work of literature.

I found four pages (here, here, here and here) on Rhizome.org listing various artistic apps (only for iPhone, which means I won’t be able to access them…). Apps related to text and language can be found on page 1, Andreas Müller and Nanika’s For All Seasons (poetry with visualisations, a gesture recalling Apollinaire’s Calligrammes) , as well as Aya Karpinska’s Shadows Never Sleep (narrative with visualisations, pictures can be found from page 25 here), and on page 4, Jason Edward Lewis and Bruno Nadeau’s Poetry for Excitable [Mobile] Media that focusses on developing new interactive relationships with texts, notably through touchscreens.

Utilitarian (if only utiliterarian!) apps:

An area of interest to me, but which lies more in geopolitics and economics than artistic practice, has been in the development of new relationships to literature and the digital sphere in China. The country has become a gigantic (and fast-growing) market for digital literature, and is turning to new technologies (especially mobile-based readership) perhaps more avidly than the West. Articles in the business press are easy to find (see here, here, herehere and here)(that last one accessible with a Goldsmiths / other university account), and the numbers are, as usual with China, quite staggering. I have been wondering for a while what it means to write for a domestic readership of 1.4 billion people, and I also wonder now about what experience these new apps (in WeChat and QQ for instance) provide. It is likely that immense majority of the books distributed there as are as insipid as most commercial production (like TV series, say), but the idea that millions of young Chinese people read novels and poetry mostly on their mobiles is quite baffling, especially coming from continental Europe, where love for the paper medium is still so strong. The main obstacle to more discovery is, obviously, language, my Mandarin being still far too primitive to dive heads on into these networks.

The web platform Rhizome developed a software for recording the Internet (based on users’ browsing habits) called Webrecorder. (But this is no app.). I should also mention their Net Art anthology website, even though this is probably again not quite what I’m looking for (websites, not apps). Faber & Faber produced The Waste Land for iPad (gathering material around the poem, including recordings, film, manuscript pages, commentary, etc.), as well as Faber Voices (presenting works of Ted Hughes, Seamus Heaney, Philip Larkin and Wendy Cope with texts and recordings). Still searching for more utilitarian apps, I found (on this page) the series of ‘serious’ apps released by Oxford University Press consisting of accessible dictionaries: mythology, etymology, idioms, philosophy, world history, literary terms, critical theory, concise mathematics (all available on the Google Play store for free, but with ads).

In a not too distant vein, I found a few apps that advertise tutorials to learn how to deal with neural networks: Artifical Neural Network, Neural Networks for Java, Learn Machine Learning : Neural Networks.

Evil apps:

Another idea, which would go in a radically opposite direction, would be to take apps that are the utter antithesis of art, and critique them from a sociological philosophical point of view: various contenders I thought of so far were the whole array of apps produced by ExxonMobil (the page for the main app contains pictures of happy African kids and an Asian dad with his daugter looking at a tablet, both also terribly happy…) or by Lockheed Martin (which seems to have produced an app offering a VR experience of the surface of Mars).

(1) Similar lists can be found here and here, with a focus on the publishing industry, and issues of production costs.

§

21 December, 11h00

There are many problems with the work Guy and I handed in this term. To my eye it is both not theoretical enough and, in fact, underdeveloped on a literary level. I will focus here only on the theoretical aspect. It is remarkable to see an old problem, one I had to deal with during my BA, MA and half-PhD in the humanities, reemerge in the exact same form.

Having chosen the topic at hand, literature and computation, I realise two things: first, that the gap I see between theory (criticism, mostly, and some of what is called ‘theory’ in the Anglo-American world) and practice (the actual writing of literature) is still very much present, as is my obsession to stay clear of the former; second, that despite my best intentions, it has proven impossible for me to muster any interest for the latter.

I can of course, as I did in the past, go through the literature, and find out who the players are, what are the landmark books, etc. I will do this later in this post. But the heart isn’t in it: I have browsed through these volumes, checked titles of articles, and all motivation to read them vanishes, leaving me with an intense feeling of emptiness and boredom. The same goes, in fact, with what could be called ‘digital authors’, namely authors that could be grouped by a participation to these ‘communities’ (be it digital or computational poetry, flarf, interactive fiction, etc.). All this seems so vain: the only authors that manage to kindle my interest are people who transcend their ‘native’ communities, who write ‘universally’, instead of ‘for a specified community’. Thus, even in my approach to literature itself (and other arts in fact), I am at odds with a ‘movement’- or ‘community’-based approach, which will focus on, say, realism, naturalism, postmodernism, or, in our case, this or that trend in those new trends of ‘computational literature’. In fact, the pull toward those ‘universal’ figures, including people having written far back in the past, is so strong that it is many times more important, more crucial to me to study their texts than any contemporary ‘digital’ author (just as it seems far more interesting to study West’s Introduction to Greek Meter, including on a computational level, than to read articles in the The Johns Hopkins Guide To Digital Media, despite the fact that the latter is really what one ‘oughts’ to read in a course on computational arts theory).

As announced, I wil now offer a brief overview of those books and articles that I could find and that could have constituted the ‘appropriate’ readings for the topic we chose:

- Aarseth, Espen J. Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

- Bachleitner, Norbert, ‘The Virtual Muse: Forms and Theory of Digital Poetry, in Theory into Poetry: New Approaches to the Lyric, ed. Eva Müller-Zettelmann and Margarete Rubik. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, 2005: 303-344.

- Bolter, J. David, Richard Grusin, and Richard A. Grusin. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press, 2000.

- Flores, Leonardo. ‘Digital Poetry’ in Ryan, Marie-Laure, Lori Emerson, and Benjamin J. Robertson, eds. The Johns Hopkins Guide To Digital Media. JHU Press, 2014.

- Funkhouser, Christopher. ‘Prehistoric Digital Poetry: An Archaeology of Forms.’ Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press. ELMCIP REPORT, 2007.

- Glazier, Loss Pequeño. Digital poetics: The making of e-poetries. University of Alabama Press, 2001.

- Hayles, N. Katherine. Writing Machines. Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press, 2002.

- —, Electronic Literature. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 2008.

- Montfort, Nick. Twisty Little Passages: An Approach to Interactive Fiction. Cambridge, MA and London : MIT Press, 2003.

- Simanowski, Roberto, Reading Moving Letters: Digital Literature in Research and Teaching. A Handbook (Mitherausgeber), Bielefeld: Transcript, 2010.

- —, Digital Art and Meaning. Reading Kinetic Poetry, Text Machines, Mapping Art, and Interactive Installations, University of Minnesota Press, 2011.

This inability to find any interest in this kind of literature (as in most of criticism, unfortunately) creates significant problems for what should have been a critical enquiry of the intersection between literature and computation. The most surprising of it all is that this is not in any way a lack of interest in abstraction or philosophy per se (although, interestingly enough, I do encounter a similar issue when thinking about philosophy and computation or new media: just as for literature, I cannot keep my eyes off certain kinds of works and certain philosophers, who interest me (almost) regardless of the subject matter they treat, whereas I fall into utter boredom as soon as I have to approach a ‘topic-defined’ field such as ‘the philosophy of new media’ or ‘the philosophy of computation). I wonder if the only resolution to this problem would not be to switch topics altogether, and instead of taking literature, my artistic focus, as the topic of my enquiry next term, I should not take something that is of theoreticalinterest, even if entirely divorced from my practice. Some of the problems I encountered will probably reappear even if I go down that route, such as the gap between my philosophical interests and the sort of topics that this course covers, but that could still be a better path than the one taken this term.

Perhaps something that could be done, despite the distance there is between this subject and my practice, would be a short study on the geopolitics of AI today, with a closer analysis on what is at stakes, what shape the race for the development of the latest systems is taking (the big competition between the US and China, the role of other countries such as Japan and South Korea, the state of Europe, etc.).

§

18 December, 22h30

One issue raised during the presentation should not be left undiscussed:

whether digital and computational literature could reshape notions of readership and authorship. In some sense, of course it could, and it does; in some other, it is difficult how most of what it introduces hasn’t been discovered and thoroughly explored by the avant-gardes of the previous century. It is possible to divide the problem into two categories: on the one hand, you have the introduction of the machine, and the mechanical, into the process of making works of literature. This is where, I would argue, nothing much is new under the sun. The other aspect, interactivity, on the other hand, could be examined later on.

The introduction of the mechanical (or the serial, perhaps, or even the methodical) within artistic disciplines has been one of the cornerstones of the 20th century avant-gardes (and, arguably, what the Anglo-American counterrevolution of ‘Postmodernism’ strove to roll back): since the early movements of abstraction the question was repeatedly raise - where is the subject? Can’t anyone do this? Where is the unicity of the work of art? And indeed, looking at the works of Mondrian, Rothko, Pollock, and countless others, one already sees a displacement of the former relationship between the painter and its technique into something that could be called a ‘methodical distance’: works exist, and truly recognisably, within a ‘methodical space’, the space in which many different ‘tokens’, variations or actualisations of the same technique can exist. The style of the artist is no longer defined between the artist and this or that detail of the painting itself, but must be sought in the method as well: it is inarguably easier to make a manual copy a Mondrian or a Rothko than it is for 19th century representational artists, but it is just as difficult to come up with a new, individual and nontrivial method that will allow one to create a series of work of equal quality. From this point of view, conceptual art went just one step further, removing the link to the materiality and craft that remained in the previous generations, to focus only on conceptual spaces.

A similar story can be told for music (with its similar ending in the return of tonality and consonance since the 70ies-80ies, mostly in the Anglo-American world), where the first experiments with method-based music were brought forward by the Second Viennese School and reinforced after World War II, leading to music that was both abstract, and yet, to the trained ear, retained the characteristics of style in this refounded system. Most post-war composers would develop systems to write their works, introducing ‘mechanical mediation’ between themselves and the notes, and a similar distanciation process happened: the major figures and major works are studied today as examples of music writing and system or method writing, where an individual artistic style can be experienced and studied.

In this sense, most of what can happen to digital and computational poetry will only be a repetition of these gestures: if you create a machine that produces random poetry, the manner in which this machine produces it, and the kind of poetry it comes up with, will not be the totality of all possible poetry. It will exist in a space of possibilities, and that space will be identical to, say, the space of potential Pollock paintings of this or that creative period, that is, the space that opens when a specific method is set up and used to produce variations. One major difference from the avant-garde works, however, seems to me to be interactivity and ‘gamification’: the avant-gardes did explore open-ended forms (especially in music and theatre), where mostly performers would have a say in how the work is created. Interactivity has also been explored by performance art and conceptual art in many different ways. However the specific angle of ‘game’, and ‘gamification’ (as most digital and computational forms, I would argue, will have to reckon with the dominant form of their medium, the video game) does not seem to have developed nearly as much.

§

13 December, 11h20

The author, the reader. My first, gut reaction is that nothing is changed, nothing fundamental. The abyss separating the ‘good’ and ‘bad’ author, artist, or body of work is still there, gaping. Reading as a specific form of engagement is still around, and what we witness more often than not in the field of computational arts is a shift from reading and literature (which remains untouched) to various forms of art (the focus being either on the artifact as a whole, as a process, often with a heavy dose of ‘retinality’, the visual aspect, which is not strictly speaking literature’s reaslm). The devil of course kicks in the details. A positive scenario for profound change could be the following: if we map literature as a whole onto theatre in the early 20th century, what would it take for computational literature to be cinema, and knock down the entire discipline from its former monopoly, take the centre stage, so that its exponents would be at the same time more widely known and, for those who reach its summit, just as highly esteemed as the greatest figures of the previous field? That would be change. Nothing such happened yet, and it is unclear that this would happen, or how.

Literature, noncomputational literature, rules unchallenged, and computation remains a curiosity of outsiders (say, amateur programmers who like science fiction), or the idiosyncratic features of some (Georges Perec, who ultimately is read not for his computational, but for what literary readers see as his ‘literary’ qualities – themes, characters, style, etc. – in our previous mapping, he wouldn’t be a film maker, but another, great, dramaturg, who happened to use cameras on stage because of his peculiar technological fancy).

§

08 December, 15h30

The question of the author & the reader. Think of a typology of possible (fundamental) changes that computation may bring in our relationship with texts.

§

08 December, 13h

It might be worth explaining one of the time-controlling functions I came up with when working with smile-related events:

if (res >= 0.8) {

if (theyAreSmiling == false) {

frame = 0;

}

theyAreSmiling = true;

}

if (res < 0.8) {

if (theyAreSmiling == true) {

theySmiled = true;

frame = 0;

}

theyAreSmiling = false;

}

The problem was: let’s say you wish to have one initial state when the program starts, and then another one if nothing (no smile) happens. For that you need to count the frames, and when frames reach a certain number, you can trigger the event you wish. However, when that event occurs, and the reader smiles, you want again that ability to control when something happens again. That would be all fine if the program were linear: at time t1, the program would start, at t2 the first event would happen, at t3 the third, etc. But in this case, you need, as it were, to go ‘back in time’: when at t2, you enter the ‘smiling space’, where this or that text happens, but if you want to go back to the first state, you need to reset time to the beginning. This, again, would be all fine, if it was ok just to go back to the initial state as if nothing had happened. If on the contrary what you want is an initial state (no smile), and after that the coexistence of two states (smile, no smile), you need to create two boolean variables, ‘theyAreSmiling’, that stores the actual state of affairs, and ‘theySmiled’, that stores the past event and switches between the initial state and the further evolution of the process.

§

07 December, 23h 59

Succeeded in creating a Shakespearean insult generator working in the same framework as the other smile sketches. I will post a link as soon as I have converted it to the P5.js.

§

07 December, 22h30

A fairly unrelated sketch, that uses the graphic powers of code, whilst attempting to go beyond the sheer ‘visual’ dimension of the letter movement by combining the sine movement with the discrepancy between the two words/letters:

§

07 December, 22h

One of the core conclusions of that project is the space that technical hurdles can take, stifling most of the creativity. I will start with an inventory of the various sketches that I've been able to put online.

The first idea Guy came up with that could combine computer vision and feasibility was to use smile detection from a library created by Brian Chung.

The sketch, first conceived to be running on processing, would interact with the web cam, retrieve the video feeds, analyse it and change the text according to the presence or absence of a smile.On that basis, and taking the smile both as a binary input and a thematic constraint, I came up with a few primitive examples of what this textual transformation could be. Given the current state of our knowledge, in the difficulties in adapting the sketches to JavaScript, these examples react to the clicking of the mouse only. The three examples also show how code allows for a complete control over what elements change (sentences, words, letters), and how they are positioned on the ‘page’.

The four examples above play with the opposition between the two moods represented by the presence or absence of a smile. In the following three, however, the tone changes to something more cutting and ironic, breaking the conventional relationship of civility between the work and the reader. Examples 6 and 7, apart from the obvious wink to the film The Matrix, are first steps into dealing with temporality, in two ways: first, through the integration of a ‘typewriter tool’ that simulates the process of typing on a screen; second, through the integration of time constraints based on the number of frames the program has been through, whereby certain events can be triggered and stopped at will. In example 6, only the first technique is used, in combination with a hypothetical smile (implemented at the click of the mouse here as well), while in example 7 each of the states (the first with no smile, the second with one, the third after the smile has stopped) is followed by another remark after a certain amount of frames, with the intent of pushing, quite curtly so I confess, the reader into smiling or stopping to do so. Working with time transforms the relationship to text quite profoundly: text has to be written like drama or music, and yet the precision is more akin to cinema or contemporary music editing than to traditional score or part writing. As often happens, the drive to expand the range of technical tools available made me neglect the actual literary work that still remains to be done (write texts of literary value but with a time constraint, or with the binary nature defined by the smile).

A third very important concept of computation comes into play in the following example: randomness. Using a random word generator studied in the Processing class, it was possible to generate a small text that plays both on the Biblical theme of Creation and this fundamental computational tool, whilst returning to the tongue-in-cheek tone of the earlier examples. If, against Einstein, one holds that creation, in the deepest sense is indeed playing dice, then randomness, even in this narrow, pseudo-form that we are dealing with here, can then be read as a pointer to the power that was attributed to God (and which is cheekily shoved onto the reader’s back): a portrait of the artist as a coin tosser. Two time-controlled events have been included as well in this sketch.

In the last two examples, the tool of randomness is explored further, following Guy’s impulsion and architecture. In the first example, this smile logic is still used, translated here as always as a click of the mouse. Each time this event occurs, a new poem is generated. Using lists of words found online, the sketch produces the text by picking randomly out of several lists of words or punctuation prepared in advance. In the second one, short poems are produced in a continuous fashion, until a face (the left button of the mouse kept pressed) is detected (This solution was developed first because the smile detection library could not be implemented on my computer. Guy proceeded to send me another version with plain face detection that we can both work on). The presence of a reader makes the computer is stop the us producing a readable version, and automatically prompts the saving of the poem into the reader’s computer.

Other versions are coming up that are not yet adapted for online use (and it is a bit of a shame not to have the video element). Various alleyways for exploration include:

- a version with more diverse dictionaries that Guy investigated, in which it is possible to toggle between different ‘styles’ of poems;

- a ‘Penelope’ prose-based version, in which random text production yields a continuous stream of text, from which randomly picked words are removed while the text is being read (once the face is no longer detected, more text is generated again on top of the one remaining).

The intrusive and potentially overwhelming aspect of the automatic saving of poems on the computer is also an interesting detail we might integrate into the final work: only a few seconds using one of these sketches generates dozens of different texts all saved at once, without any approval or oversight, into the Processing folder, adding another, very typically ‘computational’ dimension to these objects.

§

06 December, 17h

After a lot of technical issues, it was finally possible to adapt the sketches for online use. I now have a GitHub repository to host the sketches and turn them into mini-websites.

§

23 November, 17h

What could be the input received by computer vision? Various hypotheses present themselves: a typical idea would be that, from a face, the computer would be able to attribute a specific emotion to that face, and return a name for it, e.g. ‘happy’ or ‘sad’. It is hard to see how such an input could lead to nontrivial texts (that would be the challenge).

The reflex would be to try and categorise words using their meaning, associate emotions to these meanings, and therefore access these words when this face is recognised. The words would then be integrated into the text. There is still the problem that meaning in text is not just word-based, and only restricting textual modification to words will almost irretrievably produce very crude results (as a complex and subtle text will produce images, thoughts, etc., through the web of meaning produced by sentences and the whole configuration at hand, not just by elements)(A classical example of indirect meaning can be found here, a translation of Li Po by Ezra Pound, where apart from ‘grievance’ in the title no negative or positve words are used to convey the situation, which is described through social codes and allusions.)

A scenario for a ‘complete’ or ‘advanced’ artifact could be the following: a single person would have thousands of subtle facial expressions, that a computer would be able to pick up. Those many different faces would be distributed in a space, with very similar faces close to each other, and cluster of faces forming ‘emotional zones’ (sad if in that area, sad overlapping with angry, etc.), which means coordinates of a multi-dimensional space (one dimension by emotion).

Similarly, a very broad study of texts could lead to a similar spatialisation (in an ideal world it is the AI, not us, who would determine what ‘emotions’ emerge from texts, so that we would avoid the ‘corniness problem’, where we force ourselves to say, quite artificially, that this text is sad, this text happy, this text resentful, etc.). What this would allow for is a far greater subtlety in classification, most text being a very complex network of various references and emotions. Having those two spaces ready (which is already far beyond what is possible in the present context), it would be possible to produce mappings from one to the other.

Perhaps a more fruitful approach could be to use facial data in a more abstract way: use computer vision to produce any sort of data (coordinates, or subtly variating numbers depending on which expression is available), and use that data with no regards to its origin (facial expression), but simply as an input that produces variation, and on top of which tools can be developed creatively.

§

23 November, 15h

Theory Artefact

The project will include two parts: the visual one, and the textual one.

Being responsible for developing the textual one, I am assuming that I will receive a set of data as an input, and, without necessarily knowing what that input will be yet, or what form it will take, I must prepare a framework that can take in this data and process it so that it has an influence on the text at hand. My aim now will be to explore these possibilities theroretically, laying the ground for the coding work to come. A first distinction that came out in our discussions with Guy was whether the textual output should be a new or an existing text. Given my personal inclination I would prefer it if it were a new one, but both options are worth exploring. Dangers also exist in all paths: most of the time, works with preexisting texts occur because of a lack of true literary intent on the part of the author; and if this isn’t the case, it means we tread the murky, and now all too hackneyed path of Postmodernism, with its perpetual refrains of ‘there is no writing’, ‘copying and writing are one and the same’, ‘literature is ever only intertextual, thence if I add a few quotes here and there this will be literature’, and other dissatisfactions. Another, perhaps even greater, danger, is that given the limited computational skills at our disposal, even an avowed ‘original’ text could fall flat and be utterly banal, as are the near-totality of ‘computer-generated’ texts. With those caveats in mind, we can proceed. We mentioned two starkly different options: use preexisting texts, create new ones. And these two arguably exist:

creating a new poem, as intertextual as it may be (take, say, ‘Daddy’, by Sylvia Plath), is not the same as indulging in Borges-honouring thievery as can be found in the last two poems on this page. However, there is a whole spectrum of possibilities between the two, that could certainly be explored (it is perfectly possible, for instance, to create a ‘smooth’ path from any poem to any other of one’s choosing by changing only one letter at a time, thus exhibiting the underlying, virtual continuity that exist between any texts).

In order to succeed in presenting a working artifact, it will be essential to keep things simple: let us enumerate a few possibilities.

Something that can easily be done is store various possibilities as an array. Instead of having one text as a string object, I can slice it and, at various crucial spots, choose to have the computer display an element of an array. The array would contain various possibilities for that slot, and the input data would make the choice between these possibilities.

vector <string> slots = {"that lethal morning", "the hatred, the love you instill", "beigel paradise"};

string s = "London, " + slots[2] + "...";

String s would read “London, beigel paradise…”. The same process can be used at a letter (or phonetic) level: the verb ‘sing’ can be stored as an array of character, and it is possible to change the ‘i’ to ‘a’ or ‘u’ to change the tense. Similar letter swap could be used to create ‘pathways’ between words (between ‘rat’ to ‘bat’, then between ‘bat’ to ‘bot’, swapping only one letter at a time), or between entire texts (the smooth transition between one text to another mentioned above).

§

23 November, 12h

The Nonhuman Turn

In his introduction, Richard Grusin offers both an introduction to the concept of the ‘nonhuman’, the topic of the present volume, and an overview of the disciplines to which this concept can be applied (which, unsurprisingly, encompasses no less than the totality of the humanities). The nonhuman, as the name indicates, focusses on what is outside the scope of what is at least traditionally understood as belonging to the human (such as, say, affect, understanding, etc.), and this new line of enquiry aims at changing the debate in the humanities, from the previous state of the struggle where, in a very rough and inaccurate stroke, the aim of the humanities was to defend and study the ‘human’ against what was not it (e.g. the natural sciences). In a quite amusing twist which is rather typical of critical studies Grusin brings forth as his first example the concept of the ‘Anthropocene’ and puts its meaning on its head: this term, which denotes the threshold after which the distinction between the natural environment (inhuman, beyond human control) and human activity falls apart, as human activity has reached a power and importance that allows it to modify and potentially harm or destroy the natural environment as a whole, is now read as the becoming-inhuman of human activity (“humans must now be understood as climatological or on the planet that operate just as nonhumans would, independent of human will, belief, or desires”). He then goes on with the overview and discussion of this ‘turn’, which unfortunately remains anchored in the same theoretical and critical paradigm as previous ones (dominated by the same set of figures from the so-called French Theory, namely Deleuze, Derrida, Latour, etc.), and including strong contradictors (such as the so-called ‘Speculative Realists’) in one same box.

Richard Grusin, ed., The Nonhuman Turn, Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press, 2015, “Introduction”, pp. vii-xxix.

§

19 October 17, 15h

Algorithms as Imagination

Consider the following hypothesis: in a pre-algorithmic age, imagination is often described as an outside lying beyond our comprehension or control. In ancient times, the gods would represent that external intervention: the poet calls to Apollo, the Muses, or similar, for help.

In more recent times, that external realm, from which ideas and images come, can be turned inward, especially since the ‘Unconscious Turn ‘of the turn of the 20th century, the legacy of which is still with us today every time an artist invokes an unconscious decision or resources, especially dreams, seen as lying within the depth of the individual, for the source of its work and ideas. Seen more coldly, however, the ‘ gods ‘or the ‘unconscious ‘can merely be specific, singular cases in a vast reservoir of possibilities, which are ‘encountered ‘ by the artist whilst in the appropriate state of practice or pondering.

Now consider what algorithms do: they parse through possibilities and return cases, sometimes all of them, sometimes salient or relevant ones, depending on the complexity and subtlety the Artificial Intelligence underpinning them. If this view of algorithms can be held, they represent a significant steps in transforming the relationship humans have with imagination (among many other things, we focus here only on the imaginative sphere, leaving aside computation proper, conceptualisation, etc.). Indeed, instead of having the source of the imagination without, as a mythical agency, or within, as an unknowable subject, algorithms represent that stage when humanity can consciously and rationally interact with the various spaces of possibilities, as they have been able to interact with previous tools they have developed.

Let us look at an example: I develop a small program that will generate images according to some preestablished rules as well as some randomized factors. The computer will not only produce a piece of work instantly, but allow me to access a very large, possibly infinite array of ‘parallel ‘works, that are all singular instances within the space of possibilities opened by the code. Looking at all these different possible images, and how I react to them – sometimes being surprised by an unexpected shape, sometimes being provoked to tweak the code in order to produce a result but I haven’t been offered yet, but that I could infer lies somewhere in the possibilities that hand – it does feel like with the computer is offering me is a tangible, manipulable part of inspiration itself.

It is not impossible to think of neural networks in the same way: the step, this time, is that it adds a number of possible paths to the equation, the only generating a possible state and returning it to me, but generating a number of possible states, that interact in a number of possible ways with other possible states, before returning the final result(s). Again, this could be seen as all the different choices that an artist makes in the process of its praxis – but instead of remaining a possibility, they are all enacted by the machine.

§

13 October 17, 18h

Remarks on Pragmatics

A closer look at algorithms allows one to consider more carefully a crucial intersection: pragmatics, on the one hand, which usually refers to language, and, on the other, problem solving and computability. The emergence of pragmatics, as emphasized by the article (17), disrupted the self-enclosed view of language that was dominant in the mid-twentieth century, and introduced an ‘outside’ that language would interact with, in ways that exceeded previous theoretical models (what is the semantic value of a phatic expression?, how do you account for promises, orders, or blessings?).

In the case of algorithms, taken in the narrow sense of ‘a piece of code that produces a certain result in the appropriately configured machine’, the pragmatic dimension of language (code) acquires a fresh new dimension: not only, as is argued later in the chapter (18), does this blur the distinction between theory (traditionally, language) and practice (action, ‘external’ effect), as each line of code actually does something almost identical to pushing pots on a table, except at a microscopic level; but conversely it brings the ‘materiality’ of ‘action’ back into language itself, forcing us to see each bit of code as an action, a pragmatic act, and a failure or error in the code less in the traditional discrepancy between language and action (‘a broken promise’, ‘an order not followed’) but within action itself. In this way, programming a computer enacts more than ever before the unity of word and action (that was always present in mathematics, but was yet to permeate the whole of society): what you can’t think, what you can’t formulate, you can’t do. Which also means: all promises made, all orders passed into the console are enacted, followed, with inhuman/superhuman exactitude and diligence. In that sense, the right way to view an ‘order not followed’ is that the order itself was faulty, self-contradictory or nonsensical.

That at least, would have been the classical vew on the matter, that is, when it was still possible to state: ‘while formailzation comes afterwards with natural languages, with algorithms, formalization comes first’ (17). A remarkable turn in contemporary developments is that this may hold less and less, as complex procedures such as neural networks start producing results that are recognised as valid or nontrivial, while the actual detail of the process leading to such results is either unknown or being studied after the results have been produced. A very simple introduction to neural networks can reveal that even professionals with a command of the field encounter this situation where they have to study their tool closely after having tested it.

Andrew Goffey, ‘Algorithm’, in Matthew Fuller (ed.), Software Studies: A Lexicon, Cambridge MA, London: MIT Press, 2008, 15-20.

Matthew Fuller, ‘Introduction’, in Matthew Fuller (ed.), Software Studies: A Lexicon, Cambridge MA, London: MIT Press, 2008, 1-14.

§

14h

Exhibits focussing on code rather than visual (or similar) result could be compared to medieval or classical configurations relating to literature and text: scrools and books would be read aloud for an educated audience, but it is no given that everyone would read, and it would probably happen often to have an audience member receiving the literary piece without having direct access to the written text. That text would be as difficult and/or mysterious to the lay person as code is now to most people.

Manuscripts have, probably from their inception, been entangled with art practices, especially calligraphy and painting.

Marie de France, Lais, Laurence Harf (éd. & trad.), Paris: Le Livre de Poche, coll. “Lettres Gothiques”, 1990.

§

10 October 17, 18h

Lisa Nakamura’s article is the enlightening case study of an electronic manufacturing plant opened by a company called Fairchild in Navajo country in the late 60s and early 70s. The approach combines the canonical Marxian focus on labour conditions, especially the details passed over in silence by the company's communication, and a meticulous analysis of those very communication documents and brochures. It contributes to the study of the conditions and representation of what is the overlooked, almost tabooed centrepiece of global labour, coloured women in manufacturing, by examining this rare case of high-tech manufacturing and Navajo women labour.

Throughout the article, the author examines the methods by which the company portray the typical move in capitalist expansion to find cheap, not yet unionised labour as a charitable gesture fostering multiculturalism as well as nurturing the creativity of the workers.

Various strategies are to be found in the advertisement brochure:

-

One is to associate traditional craftsmanship (rugs, a woman's job in the Navajo context) with the requirements for precise and patient labour, presenting it as a ‘continuation of rather than a break from “traditional” Indian activities’ (931). Especially in a context of growing tensions given the actual labour conditions and an increasing pressur of American Indian civil movement, the Navajo, and especially the women, are depicted as the ‘ideal workforce’ (932-33), appreciated for their docility, good habits, and stoicism. The author rightly emphasises the similarity with descriptions of Mexican women in maquiladoras, ‘Orientals’ with ‘nimble fingers and passive personalities’ (933) and later Asian women (937-8).

-

The other is to present this strenuous, often damanging work in the same guise as the burgeoning digital elite pictures itself, namely as a ‘agentive or creative’ rather than ‘alienated’ (938) labour, and hail the ‘spiritual and natural qualities of high-tech manufacturing’ (931).

The Navajo workers are part of the new ‘creative class’ (925), and the whole endeavour a success story ‘pioneer[ing] the blurring of the line between wage labor and creative-cultural labor’ (931).

The article concludes with a return to Marx’ focus on labour and ‘production’, so often hidden from users, as in the example of the ‘Intel Inside’ campaign featuring clean, happy ‘bunny people’ instead of the actual workers (937), and to Baudrillard’s call for ‘another political economic based on more than just the human capacity to produce’, that is, a ‘realm beyond economic value’ (938). Paradoxically, in representing the labour of Navajo women as a ‘labour of love’ (938) the Fairchild brochure, argues Nakamura, achieves just this: ‘semiconductor production is posited as an intrinsic part of the Indian semiconductor production is posited as an intrinsic part of the Indian the “modern” world’ (938).

Lisa Nakamura, ‘Indigenous Circuits: Navajo Women and the Racialization of Early Electronic Manufacture’, American Quarterly, Vol. 66, N° 4, Dec. 2014, 919-941.

§

9 October 17, 19h

On the incomputable